Citation: “Digital Humanities Diversity as Technical Problem” Alan Liu, 15 January 2018. doi:10.5072/FK2222ZR81.

This paper was originally presented 5 January 2018 at MLA 2018, session 347 on “Varieties of Digital Humanities” (Twitter hashtags: #mla18, #s347). The original prompt to panelists (in an email from the organizers) was as follows: “The session corresponds with a planned 2019 special issue of PMLA on the same topic, and the talks at this panel may be published as an edited transcript…. Your talk would be about 10 minutes long, and we’d be interested in hearing your views on what’s next for digital humanities and/or what we can learn from what has come before.”The below version of my paper is revised to supply notes and to substitute links or references for slide images. Another change: two paragraphs elided at the live event due to lack of time–on “DH Re-imagination of Time-Space” and “Rhetorical DH”–are here included.

Clearly, there are further research directions for “digital humanities diversity as technical problem” to be explored beyond those I sketch here, but these are a beginning agenda.

15 January 2018

Our “Varieties of DH” panel addresses the methodological and social diversity of the digital humanities, in part by drawing on the digital humanities meme of the “big tent,” originally the declared theme of the international DH conference when it was held at Stanford University in 2011.[1] To quote the program description for our panel today, DH is “expansive, movable, but precarious, a tent still not big enough in terms of diversity and access.”[2]

The “big tent” metaphor, of course, comes down to us from old-timey showcases of mass experience such as nineteenth-century tent revivals and big-top circuses. Those were just two of the mass architectures, apparatuses, institutions, and (to use Foucault’s word) dispositifs whose paradoxically open and enclosed forms stage-managed the modernizing encounter (variously democratic, cultic, or fascist) between an older, affinity-based sense of the Volk and the newer awareness–at once enraptured, entertained, and appalled–of social, racial, linguistic, geopolitical, and even “special” in the sense of cross-species) variety.  Circuses, for example, were spectacles of variety. As advertised in a nineteenth-century Barnum & Bailey poster, they are “a glance at the great ethnological congress” and also menagerie of “curious . . . animals.”[3] We can add earlier and later examples to the catalogue of paradoxically open/closed, inclusive/exclusive variety–for instance, the French Revolutionary Champs de Mars, whose remaking for the 1790 Fête of Federation famously convened Parisians both low and high[4]; Albert Speer’s “cathedral of light” (Lichtdom) ringed by searchlights at the Nuremberg Nazi rallies; and today’s conceptual architecture of “open source” programming (not the “cathedral,” Eric Raymond memorably said, but the “bazaar”).[5]

Circuses, for example, were spectacles of variety. As advertised in a nineteenth-century Barnum & Bailey poster, they are “a glance at the great ethnological congress” and also menagerie of “curious . . . animals.”[3] We can add earlier and later examples to the catalogue of paradoxically open/closed, inclusive/exclusive variety–for instance, the French Revolutionary Champs de Mars, whose remaking for the 1790 Fête of Federation famously convened Parisians both low and high[4]; Albert Speer’s “cathedral of light” (Lichtdom) ringed by searchlights at the Nuremberg Nazi rallies; and today’s conceptual architecture of “open source” programming (not the “cathedral,” Eric Raymond memorably said, but the “bazaar”).[5]

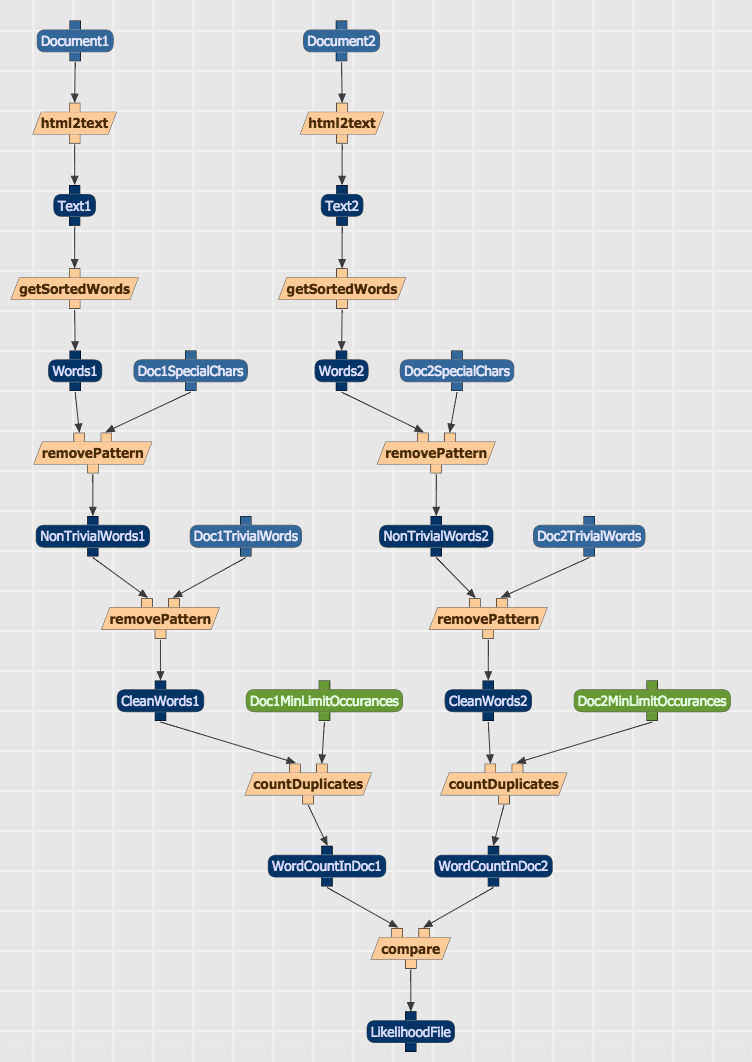

What’s next for DH? I think what’s next is finally to put the “big tent” metaphor to rest. We need new paradigms and dispositifs or, in computer-speak, platforms for diversity that move the modern democratic paradox of open and closed (inclusive and exclusive) beyond nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century paradigms of mass “variety,” beyond the mid- to late-twentieth-century scientizing of such variety as statistical socioeconomics, and likely also beyond current “bags of words” cultural analytics approaches, which bring up the rear with topic models and other congregations of language standing in for the big tent (or bag) of mass human experience.

Among other things, in other words, diversity is a technical problem….

Blog Essays , Uncategorized

Blog Essays , Uncategorized